|

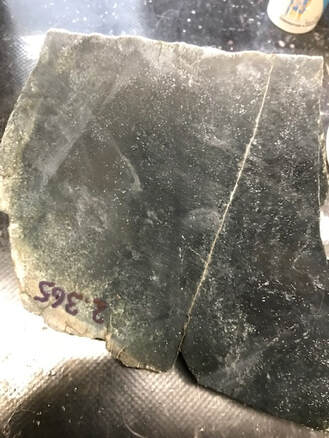

No two pieces of nephrite are the same. Most have a range of crystal sizes, and many have the variations across even small sections of stone. Only the best quality stone has an even, cryptocrystalline (very, very fine) texture throughout, and with no veins or fractures through it. That’s why some pieces of stone are more expensive than others. It’s generally the case that you get what you pay for. A piece of nephrite with coarse, or variable crystal sizes will never give a mirror finish across the whole piece, but you will be able to polish any finer crystalline areas to a high sheen. The variation can give character to a piece!

There are often clues found on the exterior of a piece of jade as to its interior texture and structure – you might see a vein for example. But let’s just stop here for a moment. What’s the difference between a vein and a fracture? A fracture is a crack in the rock. I’m not going to talk about “open” (unfilled) fractures here - you must plan your workpieces to avoid them, though superglue can sometimes help to stabilise a worrying, small fracture in late-stage finishing.

Fractures occur:

Some of these fractures fill with mineral-rich fluids in the ground, which deposit the mineral salts they carry and close the fracture – and those become the veins I’m talking about here. So, the mineralogy of the vein filling may be completely different to that of the jade, depending on the temperature and pressure of the rock and what minerals were mobilised by groundwater or geothermal fluids at the time. As a result they may be harder or softer than the host jade. So let’s get back to the piece of fictitious rough you are looking at. You may also see several sets of sub-parallel fractures defining the sides of the piece. These come-and-go, merge with other planes of fracture and/or define changes in the structure of the rock – possible hangovers from the original lithology of the piece before re/crystallisation began. You might see depositional features like traces of ancient algae or different crystal sizes representing different sized sedimentary grains, and even reflecting the different lithologies of the original sedimentary rock. To see more subtle variations in crystal size you probably need to cut and slab your piece of rock. But to really find out the quality of the stone you may have to polish a face. If the crystal size is even across the face, you are onto a winner. It certainly makes carving easier. If there are more highly polished, raised veins you have a piece of rock with a bit of a history. Or there might be small, irregular areas protruding or sunken into the face by just a few microns after you’ve polished it, reflecting different hardnesses and chemical compositions for the two parts - the softer areas are undercut preferentially to the harder parts. It’s not the end of the world – just be aware of it when you design your piece or plan the finish. According to Len Gale in his book “Greenstone Carving, A skillbase of techniques and concepts” (published by Reed Publishing (NZ Ltd), pendants were historically only given a matt finish by Maori carvers, and there has been a renewed trend to leaving faces or entire pieces with a satin or matt finish over the last 20 years in NZ. I’ve found that leaving one face rough on a simple pendant creates interest and people snap them up. If however you want a mirror finish on the piece you need to be aware of the hardness variations in your rock and choose not just the right piece of stone for your work but the right part of the right piece.

Of course, you are most likely to only discover the variations once you get down to the final pre-polish stage of, say, 1000 grit. Life can be like that!

There are ways of dealing with undercutting of the softer material, like preferentially and carefully grinding the higher, harder areas, and then re-finishing the piece with a minimum of work. Or you can also rub it all down again and leave it with a satin finish which will hide the softer material, which often doesn’t take such a high polish. And one last point. A piece of semi-nephrite (a piece of stone not completely recrystallized as nephrite) will be likely to have parts of the original, precursor, rock remaining. These will have a different mineralogy to the areas which have melted and re/crystallized. They may pose difficulties, and may break more easily than the rest of the stone, so it will be worth using this rock for making chunkier pieces. Turn it to your advantage! So the next time you buy some jade, you need to look at not just the colouring, but every aspect of the rock, as the outside carries clues to what’s inside, and also how you should cut it, but that’s a different subject entirely!

0 Comments

|

AuthorOn this page I intend to add monthly updates on aspects of jade carving. I also plan to invite more experienced carvers to offer a "master-class" on a particular subject of their choice. With this I hope to enthuse both the novice and the expert in this ancient and beautiful art-form/craft. And comments are welcome! Archives

March 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed