|

We come to almost the final operation in the production of most pieces of work – the polishing. That’s not to say you have to polish every piece to a high gloss as you can also choose to leave them natural and rough (so long as they don’t scratch the wearer), or smooth with a matt or satin finish if you prefer. And you don’t need to polish every face – employ variation as a means of creating interest and highlights in a workpiece. Each piece of stone is unique, and there are often very local variations in hardness, crystal size, texture, the numbers and size of inclusions and the fabric in each piece of stone. Some crystals are softer and undercut quite easily. And the alignment of the crystals in a rock will affect the degree of polish you can impart - most rocks polish better in one direction than another. If this only becomes apparent as you are polishing it you hope you cut the stone the right way to allow the best shine on the most important face! With all of these variables, eventually, you will reach the limit of polishing and may not be able to achieve a “perfect” finish. But if you aren’t happy with what you’ve achieved, take it back with a light re-grind with 600 grit and then progress again towards the polishing stage – it generally does produce a better finish the second time as the preparation was more thorough than the first. So, back to my story: looking at the workpiece which you have just pre-polished by grinding it on a dull 600 grit lap, or a 1500 grit flexible diamond belt, or hand-ground it using 3000 grit sticks (different grain sizes can produce a similar finish in work), you decide it needs to be polished. Well, as in all things carving, there are a number of different methods you can use which I’ll go through below. Laps with Wet & Dry paper Buddy showed me his method (see the section on laps for more information on general use) and achieves far better results than I can with it. See, practice does pay off!

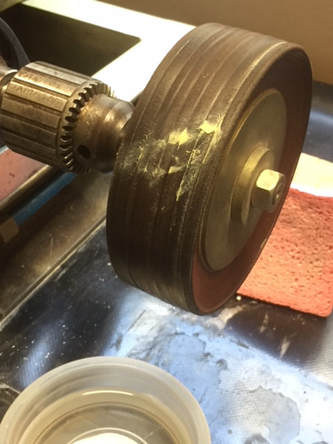

So practice, practice, practice! High-chrome leather disks Steve uses this method and achieves fabulous results with it! To begin with, you need to find someone who can provide you with maybe 10 high-chrome flat leather disks of 150 - 200 mm diameter and 5 mm thick with a certain sized hole punched in the centre to mount onto a mandrel and clamp them in place. See Picture 1 below. If you follow this route to polishing nephrite, you need to use diamond paste, which you apply to the working (curved, outer edge) face of the leather. It becomes embedded in the leather and means one application of not very much (the amount is about the size of a match-head) will charge the wheel for maybe 15 minutes of working. I use 50,000 grit (half a micron) paste on mine and I achieve satisfactory results. You can also buy coarser, 12 - 14,000 grit paste, but it doesn’t give as high a polish on nephrite using this method in my experience. Once you have decided on a particular grain size to use on your polishing wheel you need to stick to it – you can’t change, except to go coarser, which defeats the object!  Picture 1 on left shows the leather wheel (once 150 mm diameter but now worn down to 135 mm) with a smear of diamond paste across the working face and ready to go. You can also see the dip container filled with water and a strategically placed sponge and wooden block behind to stop flying pieces hitting the wall. It's better to be safe than sorry. To begin with, you set your equipment to a slow rate of rotation – I use 600 – 750 rpm. You need the leather damp, not wet. Sitting in front of it (wear eye-protection in case of paste or water drops flicking off as it rotates, as well as the occasional workpiece) you smear a couple of match-heads of the paste across the face, and rub it in to stop it being flicked off when starting the wheel. You will need a small bowl of water in front of you, with which to cool the piece and your fingers, and to dampen the leather. I use a small plastic tub, purchased from a supermarket with a dip in it, as being the perfect size. You need to dampen the face of the leather, by dipping your fingers into the water and wiping them on the working face. The water is quickly absorbed. Turn on the power and lightly apply your workpiece to the leather. The leather can be too wet, or too dry. To polish best it needs to be “just right” – a term which I can’t define - but you will find at some point after polishing for a while that you hit a “sweet spot” where the polishing goes more quickly and you get great results. Keep adding water at the same rate and stop and apply more diamond paste when the rate of polishing slows. Your workpiece heats up with friction from the wheel. The water will cool both fingers and work. Keep dipping! Don’t press too hard or you can virtually stop the wheel, which isn’t good for the windings of your motor, which quickly overheat. Sometimes I feel as if the surface of the stone has melted with the friction. A beautiful, high polish suddenly develops at a time when the wheel was prone to slowing down due to that friction. Does it really melt? I don’t know. The face of your wheel needs to be scraped down occasionally to keep it as concentric and “square” as possible. This reduces bounce on the wheel. I use an offcut of nephrite with a straight, sharp edge, which I scrape over the leather (when the power is off) and which reduces the high points which develop, as well as scraping the polished leather off so allowing paste and water to be absorbed into the leather, which facilitates the polishing of your work. And a final note - keep your wheel covered when not in use – dust can scratch your future work. This article will be completed next month ....

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorOn this page I intend to add monthly updates on aspects of jade carving. I also plan to invite more experienced carvers to offer a "master-class" on a particular subject of their choice. With this I hope to enthuse both the novice and the expert in this ancient and beautiful art-form/craft. And comments are welcome! Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed